Adrian Lane is an artist and musician based in Southend-on-Sea, Essex. As somebody whose work I’ve admired for many years, and as someone who continually sets the bar higher and higher with every new release, I was keen to get in touch with Adrian to discuss his working practices.

Knowing that a time would come where I would need to write this, I’ve been trying to think of how one could describe what Adrian does by way of a short introduction. I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s an impossible task; his music is by turns gentle and abrasive, rigid and fluid, simple and intricate, both contemporary and ancient-sounding, light and dark, serious and playful. There are shades of ambient, electronica, experimental, classical, field recordings, and musique concrète spread across an ever-expanding back catalogue; which moves from the eerie 100-year-old-wax-cylinder-sampling ‘Playing With Ghosts’ (2017) to the prepared piano and strings of 2019’s ‘I Have Promises To Keep’. That’s not to mention the blurring of the lines between the synthetic and the real on 2020’s ‘Indigo and Salt Peter’, and the superb eponymous collaboration with Guido Lusetti under the name That Faint Light (2017) that plays out like a lost soundtrack to a film that never existed.

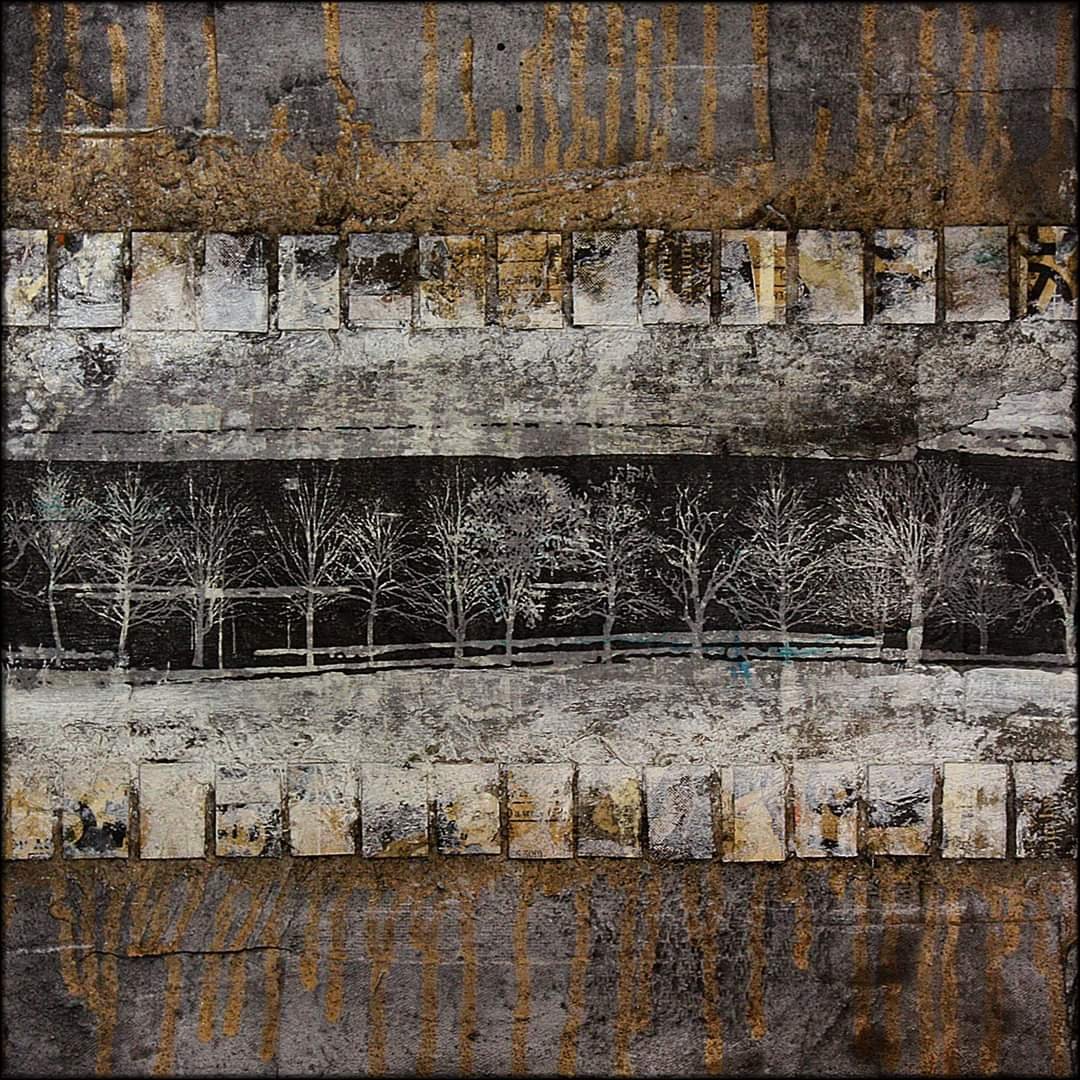

Much like the mixed-media paintings that adorn his record sleeves, Adrian’s music is often the result of a delicate layering of disparate elements that come together to form a distinctive, instantly recognisable sound that seems to evolve a little bit more from record to record. It’s this evolution that intrigues me most about Adrian’s music, and seems as good a place as any to begin our conversation — how does one go from playing unhinged guitar in a post-punk band to composing the delicate upright piano and field recordings of ‘Lekko Sketches’ (2020)?

(Note: To make things easy to follow, my questions will be reproduced in bold and Adrian’s comments in plain text).

• If one were to trace a line through your work, there’s very interesting development in terms of where your music is now compared to where it was, say, ten years ago. Was there a specific moment when you decided that you wanted to move away from lyrics and more conventional song structures, or did it evolve naturally?

I have been listening to instrumental music since I was a teenager, and the music that I come back to from that period tends to be more of the instrumental pieces rather than the song based pieces from more traditional band line-ups. As well as playing in bands, when I was a teenager I also used to play around with writing instrumental pieces on synths, guitars and samplers but never really produced pieces that I thought were good enough to share with a wider audience. Part of that was due to my own immaturity as a musician, but a lot was also due to the technology available to me at the time. I was producing pieces inspired by the likes of Philip Glass, Brian Eno, Arvo Part and Steve Reich (to name a few), without access to a whole range of classical musicians and a high end studio that they would have had, and I think my ambition was far greater than my capabilities, so I kept those pieces to myself.

In recent years the technology has evolved so much that a lot of what would have cost thousands of pounds in equipment or studio time can now be achieved with a relatively modest budget on a home computer. I am now able to achieve what I set out to many years ago. In the last 10 years I have found myself listening to less and less song based music. I still really like certain songwriters but never seem to feel like listening to them; I maybe listen to an album with vocals on (in the sense of traditional song-writing) twice a month, whilst I listen to instrumental music every-day. Therefore my return to my own instrumental music is really a response to my own listening.

• To what extent do you feel as though your music is ‘about’ something? I mean, when you begin a project do you have a particular image in mind? There is a distinctly different feel, for example, between the music of ‘Branches Never Remember’ and ‘Atlas Browsing’ that goes beyond the differences in instrumentation.

Whenever I produce an album I have a basic concept in mind, which goes with certain feelings I want to express. I sometimes have several projects on the go at once, but group tracks in terms of the feeling I get from them and also the musical approach and palette of sounds used. The individual tracks don’t really have a specific narrative, but are about something more intangible, that I find difficult to express in words. Having said that, there are certain tracks on my recent albums, Lekko Sketches, Atlas Browsing, and Indigo and Salt Peter, which are a direct response to the current situation with the Covid-19 pandemic. For example; the track ‘Across Empty Squares’ was inspired by images I saw on the news, of the squares in Italy that usually would be busy almost all the time but were deserted.

I have never been the most talkative of people and I think I use music to express what I can’t verbally. Maybe that is also a reason that I moved away from song-writing, in that I felt I wasn’t able to express as wide a range of themes lyrically.

• To me, the artwork that accompanies your records always feels as important a part of them as the music. With that in mind, I was wondering how important a part of the overall experience you find the relationship between the visual imagery and the music to be. Do the two typically develop symbiotically or do you create the artwork in response to the finished music? I guess that, in a roundabout way, I’m getting at whether you see music as just another facet of your practice as an artist…

For me, the artwork and the music are really part of the same thing and my working methods on each are quite similar. Occasionally, I will produce a painting specifically to go with an album, but often the paintings that end up becoming covers are pieces I was working on in the same time period so they seem to automatically link, as I have been responding to the same stimulus.

When I paint I tend to build up in layers and often include collage elements, reacting to each successive layer as I add the next. Certain layers get obscured and are barely or not at all visible in the final painting but are important in the development of the piece.

The music often starts as a short phrase on one instrument and then I will add another instrument over that. Then as that is done I’ll extend it into a new section and see where that leads, the music is effectively being recorded as it is being written. Technology allows me to cut and paste parts to hear how they work together, structuring the piece as I go along until I feel it is finished. I’ll add bits, remove bits and mix certain elements very low so they are barely audible building up the overall texture. I very rarely sit at a piano, for example, and write each section of a piece and then record it; a piece will evolve much like the paintings.

• In terms of artists that have influenced you; how have they changed over the years? And is there a constant throughline or a particular quality that links them?

I have many favourite artists that I have listened to over the years, but the ones that have had the most direct and long-lasting influence would be David Sylvian, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Philip Glass, Steve Reich and Erik Satie. There are probably only 6 or 7 pieces (Gnossiennes and Gymnopedies) of Satie’s that I listen to, but these pieces have stayed with me since I discovered them when I was about 18 years old. I have been listening to David Sylvian’s music since I was about 13 years old and the melancholy nature of his music had a big influence on me. I admire the way he has continued to explore and the fact that although he is a singer he has also released quite a few instrumental records. As a teenager, it was listening to his music that made me discover a whole host of other artists that he had collaborated with such as Jon Hassell, Danny Thompson, Kenny Wheeler, Robert Fripp and Christian Fennesz.

In terms of a link between these artists, I think each of these artists have a meditative and maybe slightly melancholy quality that has always appealed and that I strive to achieve in my own work.

• You’ve released a number of albums through the Preserved Sound label. With small labels and venues now feeling the effects of the COVID fallout, how important do you think labels like Preserved Sound are for the future of non-mainstream music?

I think labels like Preserved Sound (and Whitelabrecs and Hibernate who I have recently released albums for) are very important for the future of non-mainstream music in that although it is very easy to put out music on your own these days, having a label supporting the music gives it more legitimacy. For example; I follow a number of labels through the Bandcamp platform, and I will listen to their new releases because I trust the curation of the releases and I know I have liked albums they have released in the past. It means I will listen to music by artists I have never heard of, that I maybe would not otherwise. That is not to say there is not a lot of great music out there that is self-released, as I have discovered some excellent stuff just by browsing genres.

One advantage that these small labels have in the current climate is that they are labours of love. The labels are not releasing music with the idea of making huge profits, they are doing it because they love the music. The people who run these labels usually have day jobs, and that means they can hopefully be more resilient in the current climate as the label is not supporting people’s livelihoods. The same applies to the musicians who release this kind of music, if my aim was to make loads of money, I certainly wouldn’t be releasing music with no drums and no vocals. Obviously, I would like to reach a wider audience, but I don’t have to do that to survive. The most important thing for me is to be able to produce the music and hopefully it will resonate with some people. I realise I have quite a small audience but it is gratifying to find, through stats on various streaming sites, that I have listeners in Japan, Poland, Russia, Taiwan, Hong Kong, US, Peru and UK, for example.

• With regards to a label like Preserved Sound – I was wondering if, and how, you think that being part of the label (and the community of artists around it) has been important to you…

Being part of the Preserved Sound label has really given me the opportunity to get my music out to people who would not normally have heard it, and I am very grateful for their support. The label does not describe itself as a ‘destination’ label, and many of the artists have released on other labels too; my recent albums released by Hibernate, and Whitelabrecs, but it is definitely a label I would like to continue working with, and we plan to release a new CD later in the year (one that was put on hold largely due to the pandemic).

• I’m always drawn to your track titles. From my own limited experience, I find it’s always easy to title a track that has lyrics but less so a track that is instrumental. Where do your titles tend to come from, and do they typically arrive before or after the track takes shape?

I do find coming up with track titles difficult, and they tend to come after the music, although the initial idea for the title will often be there fairly near the start of the process. Working as I do, constructing the pieces using the computer, I obviously need to save the work and I try to come up with a basic title at the point of the first ‘save’. I have found from experience that saving as ‘untitled 1, 2, 3’ etc. can mean I lose track of what is what. I tend to browse through any books I have lying around to pick out certain words or phrases that I feel fit with what has been produced so far, sometimes these titles stick or sometimes they change slightly but usually the basic idea is established. I will also note down any phrases I like in a notebook for potential use as titles; sometimes I also cut phrases or individual words from magazine and newspapers and reassemble them into titles. If I am lucky, a title will pop in to my head because of the theme of the track, and I can just name it there and then (as was the case with ‘Across Empty Squares’).

• One of my favourite projects of yours is your 2017 collaborative album with Guido Lusetti, That Faint Light. The blurb on Bandcamp describes it as ‘a style that neither could have conceived on his own’. As I understand it (and I could be wrong!) this was a project that was completed entirely remotely. Where do you even begin with a project like this?

Yes, it was produced entirely remotely; myself and Guido did not meet until the album was virtually finished (when we met briefly for a couple of hours when he had a short holiday in London). The project started through mutual appreciation of each other’s music on Soundcloud with a few comments and messages going back and forth. Then one or us, I can’t remember which, suggested we try working on something together. For each track one of us would come up with an initial idea; for example, I would record a few phrases on the bowed psaltery, and then send it to the other. The other would then add some parts and then send it back, and so on until we felt it was complete. We would obviously make suggestions and comments on the pieces the other had added, but luckily the process went very smoothly with neither of us requiring the other to make many alterations to what they sent. The tracks were constructed in a similar way to how I work anyway, just with another person adding certain layers, so it felt quite natural to work that way. It was interesting as Guido would sometimes hear things in a completely different way to I had in mind, for example, placing the start of the bar at a different point of the phrase, to where I had it.

I have recently worked on another collaborative project, where a group of 10 artists have all written the basic skeleton of a track, which has been sent to the others to write parts over without hearing anyone else’s contribution. These parts have then been sent to the artist who wrote the original skeleton to mix and structure; a kind of blind collaboration. As yet, I haven’t heard what the others have done with my contributions to their tracks but I had some really interesting parts sent back to me for mine.

• You seem to have been even more prolific in terms of your output over the last few months, with a trio of albums released – Lekko Sketches, Indigo and Salt Peter, and Atlas Browsing. Is it fair to say that the lockdown period has been a productive time for you and, if so, how?

One of the things I always got frustrated with was not having enough time to work on my art and music. Working full-time as a college teacher often means that by the time I get home from work I am exhausted. I often find I have ideas, but don’t have the energy or the time to work on them. Although during the lockdown period I have still been working, it has been from home. This meant that I avoided the fairly long commute (often an hour or 90 minutes a day), and although it was tiring sitting at a computer for what was sometime longer than I usually would have been at work, I did not feel as tired. Most of my students are great, but being around teenagers all day can be exhausting; and somehow they didn’t tire me out as much when they were at the other end of a Teams lesson (I didn’t have to constantly tell them to stop eating and drinking for a start).

I found myself with more energy, and because I basically had no option but to stay at home, I spent all my free time working on music and painting, so produced in 3 months what would usually have taken me over a year. At times during the pandemic I have felt very anxious, but I have tried to stay positive and channel everything into the music. I realise that so far, I have had it easy compared to many people, so have made use of the time that has been made available to me. I would like to look back on this period, with a sense that I have achieved something, despite the difficult situation.

I just want to say a huge thank you to Adrian for to taking the time to speak with me. It’s always interesting for me to delve into an artist’s working practices and hear about the work that goes into the work, so to speak, and I hope that it resonates with others too. If you’re reading this and you haven’t done so already, then you can check out Adrian’s stuff on Bandcamp, Facebook or Spotify.

Leave a comment